An interview with playwright Samuel Harps about the subject of his new play, Paul Cuffe

Interview and portraits by Merri Cyr Edited and written by Paula Gauthier

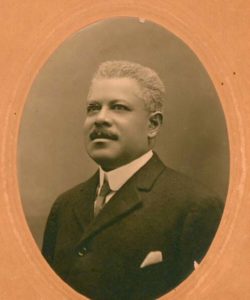

Samuel Harps

Photo by Merri Cyr

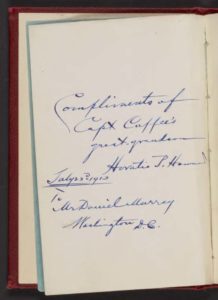

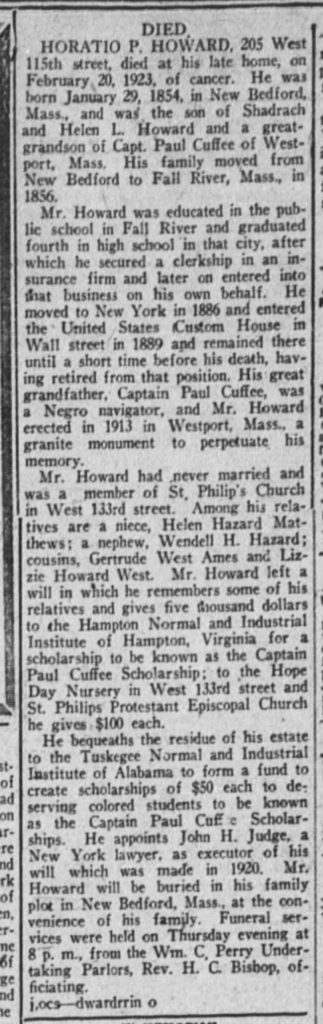

Award-winning playwright Samuel Harps presented a public reading of his new work-in-progress, Paul Cuffe: In Search of a New Land, to a packed house at the DeDee Shattuck Gallery in Westport on September 9, 2022. Harps wrote and directed the play based on the life of Captain Paul Cuffe, the prominent Quaker merchant, ship captain, and abolitionist. The evening was sponsored by the Westport Historical Society and funded by the Westport Cultural Council. Harps is the founder and artistic director of Shades Repertory Theater in Rockland County, NY. In researching this play, he consulted the Westport Historical Society who provided access to their archives, which included Captain Cuffe’s personal letters and correspondence. Westport Cultural Council member Merri Cyr met with Samuel Harps on his recent visit to Westport to discuss his journey to learn about the life of Paul Cuffe.

Merri Cyr: How did you come to write a play about Paul Cuffe?

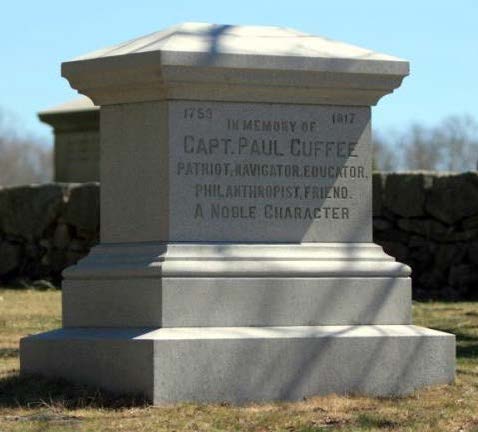

Samuel Harps: I was humbled and also embarrassed that I hadn’t heard of him. I was raised as an Army brat so my early years were spent in Germany, but even our history books just didn’t cover the broad scope of African American history. On my first visit to Westport, at a book sale, I stumbled across a book of African American whalers in New Bedford and Newport. The book sale was at the Westport Friends Society, and a gentleman came up, John, and he said, ‘You’re interested in Paul Cuffe?’ And that’s when the doors, if you will, Pandora’s Box just opened up. He said his grave is right back here; come I’ll show you. He showed me his wife’s grave and his grave, the original stump where he started building a schoolhouse. It was the 200th anniversary of his death – he died in 1817 – so to stumble across someone I had never heard of in the town that he’s the favorite son – I mean they love Paul Cuffe here – that was great for me. His story was so big that it was incredible, so I tried to tackle it as a playwright.

MC: You chose to focus on the latter part of his life but how did you start to go about writing this story?

SH: I had an abundance of books on his life, so it started with just reading who he was. But the key was reaching out to the Historical Society. They had all the facts: the numbers and his success, but more than that they had access to his letters, his journals, letters to his wife, his friends and family. And as an artist, that’s how I came to know who Paul Cuffe was. Just at the time when we were about to do a reading of a first draft, the pandemic hit. Our theater in Rockland County had closed down and I had time suddenly to really look over all of his letters to get a rounded idea of who he was and his struggles. An African American Native American during that period, respectfully to the Historical Society, it sometimes looked pretty easy the way it was done. He was able to meet the president, he was able to travel around the world. But in his letters, his correspondence to his friends and family of African American descent and those closest to him, he talked about how tough it was to do that.

I wanted to bring in the external antagonistic forces. There was a huge slave trade going on around the world but especially Newport and New Bedford. A lot of the merchant ships here that would take corn and wheat and lumber also had many slaves at the very bottom. I wanted to focus on all of the external obstacles because that was Paul Cuffe’s motivation, to stop the slave trade. His life was so big that I decided to narrow it down. He was one of the key factors in colonizing Sierra Leone as a free colony for freed slaves. What he set out to do – and I’m focusing on the years between 1808 and his death in 1817 – my play focuses literally on him getting 10 families, 38 African Americans, from here to Sierra Leone, which took up a huge part of his 40s and 50s. That just became the story.

MC: What were the obstacles you came up against and how are you working through it?

SH: My first stumbling block was trying to write a story that was too big. It’s not an autobiography. The people in Westport know things that you can Google about Paul Cuffe. They know where he was born, where he was raised, his family ties. I went into it with the model that if you can Google it, then it’s not terribly important. The Historical Society, I had a meeting with the first draft and it was eye opening because they were able to get the facts right precisely, the dates and the times, which are important for me as a writer. I’m not a historian and I’m not an academic; I’m a playwright. I had to try to fuse those together and create a person out of Paul Cuffe, that’s not just numbers, dates, figures. So that’s where his letters, correspondence, his personal letters, that was when the story opened up for me. And I literally had to start over. I tossed the first draft.

MC: Paul Cuffe was able to move in society in ways that other black people weren’t able to do. What do you think it is about his personality that allowed him to travel in this society?

SH: He was a big personality. I guess for the time he could be considered an influencer because he was very charismatic and also he was very wealthy. When he was writing to other businesspeople, he was very shrewd. But he did it in a very quiet way. ‘You owe me money. I need it right away. Your trusted friend, Paul Cuffe.’ You know, but his third letter down would be: ‘I didn’t get my money. I still need my money. Your trusted friend, Paul Cuffe.’ He was very religious of course and very family oriented. All of his businesses were started by his family and family run. Paul Cuffe was of Native American African American descent, so he was of a caramel color you know. And what’s funny about that is the term still lingers: interracial racism. Where a man my color might not have been able to do as much as he did, money or no money. Because he’s mixed, that helped, but more than anything he knew how to influence people and he knew how to get in touch with the right people.

MC: Can you talk about him, how he was in this Westport community? I just can’t imagine it was that easy for him. How did he live in a racist environment and yet prosper?

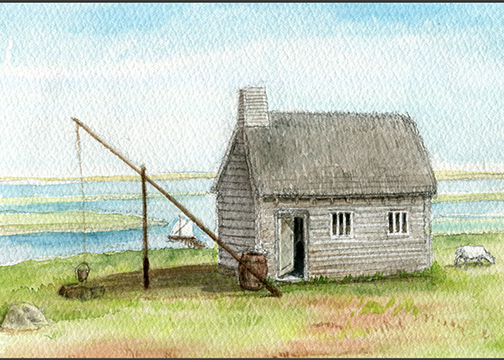

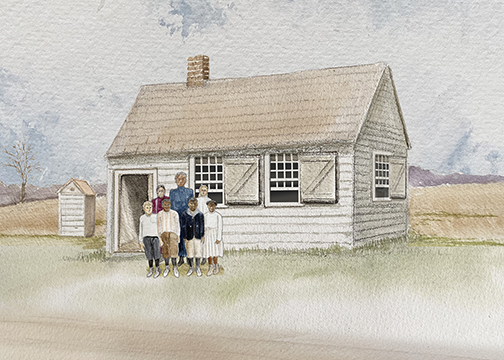

SH: You know that he and his brother petitioned the state of Massachusetts because they weren’t allowed to vote, so you know he had those obstacles. He did write of incidents that he had come across with slave traders. His nephew Thomas had gotten nabbed in the slave trade. This was 50 years before the Civil War, and New York, Massachusetts, were, I guess you would call them lenient, but there were still slaves and slavery here. Not that people here were cruel, but not everyone was kind to Paul Cuffe because he’s not like them. He built the school on his property initially for his own kids and he walked around town and told everyone this school is open to anyone who wants to come, if you want to be a part of building this. But no one was terribly interested in doing it. No one wanted a Paul Cuffe school. And there were people that didn’t want a Paul Cuffe. Once he built the school for his kids he opened it up for all of Westport and that gave him a connection to the people. He opened up his doors and they started to open up theirs. Paul was raised a Quaker and became a member of the Westport Society of Friends, who were instrumental in getting him a connection to not only people in Westport but throughout the United States and abroad.

MC: The reading of your play – this work-in-progress – is an opportunity for you to see it performed in front of a live audience. What does it mean to you to see it performed?

SH: My idea was to bring the audience in at the beginning of the process, which we would normally do at our theater but it’s no longer there. We would bring in an audience just to hear what it sounds like. It’s good to have an audience because you get a chance to see what moves people, what makes them laugh, what makes them uncomfortable and makes them wiggle, you know?

MC: How many characters are in the play?

SH: At this reading we have 10 actors that are reading the parts of 13 people. Overall, the final cast will be 15 because I’ll have the actors in every role. Most of the play takes place on ship, which was important to me to show that he was a ship captain first and foremost. He was a seaman, a sailor, and he loved the ocean and the sea. He talked about being on the water and what sailing meant to him. And the same with his family. His nephew is in the play, his son is in the play, his brother-in-law Michael Wainer is in the play. His wife is in the play, Alice. His son, nephews, and brothers built his ship and they manned his ship. It was one of the few all black crews in the world. When he traveled around he had some obstacles. He got stopped outside of Russia and this is where he got his first white apprentice, a young man, who had never seen a black person. He’d never seen a black crew. And he left with them and stayed with Paul Cuffe and his crew for the rest of his life. Other places he had gotten stopped because they thought he was harboring slaves. He had a crew of 26 African Americans and you can’t explain it; that this was his ship. And those are the things that are in the play.

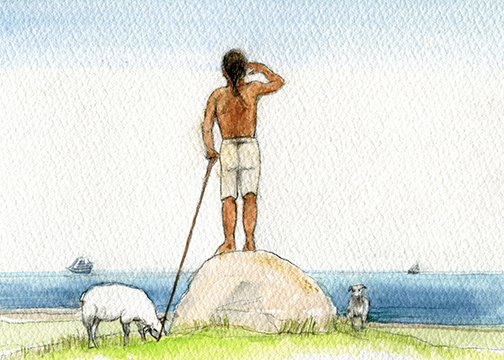

MC: Can you describe to me how you see him? How you see Paul Cuffe as a person?

SH: He’s about 6 foot even and he’s a stocky man; he’s solid. He has a very deep distinguished voice. I can feel that when I read his stuff. But he’s soft spoken when he’s talking to his son, his wife, his family, his animals. He was a gardener, and he was a farmer and he’s a very religious man. He prayed daily not just before meals and everything. When he set sail and every time he brought his crew up to the deck he prayed, so he’s very soulful, religious. And in a Quaker sense, that’s what was beautiful because the Quakers see it, we all have the light of God in us. That message resonated with me especially, so I started to feel him. As a writer, I’ve written about Harriet Tubman, I’ve written about Frederick Douglass and characters that are bigger than life. But what was special about Paul Cuffe was I felt him when I started to write dialogue for him. Because the letters, you know sitting in a quiet room reading his letters, I started to really feel what his voice sounds like, what he looks like, from how he wrote.

MC: What do you like about Paul Cuffe, the way that you have come to know him?

SH: That he was actually witty. He was funny. And his sense of spirituality is really touching. His dedication to his interpretation of God, that was very important. I’ve been writing this play for 3 years now but I’ve not been living this play. I’ve not lived it yet. In 2017, by 2018 I would have read it with actors around the table and rewrote it based on what I heard. And then I would talk to my actors about what they heard and then I would rewrite. And we would go back and forth and that’s the process. We would discover who Paul Cuffe is. When those relationships happen onstage or in the process, a story evolves and personalities evolve. I’m a writer that loves the process and my actors love the process. I’ve not worked on a play, I don’t think this long, thanks to the 2 years of the pandemic. But it was one of those happenstances that was perfect. I was looking for something to do and that gave me something to do. Hours and hours of finding out who he is. I’m still discovering who Paul Cuffe is.