And Some Interesting Related Stories by David C. Cole

In 1851, James B. Congdon, the Director of the New Bedford Free Public Library and an early researcher into the life of Paul Cuffe, apparently invited Ruth Cuffe to write down her memories about how her grandfather, Cuff Slocum, gained his freedom. That document, preserved in the Library’s collection of papers relating to Paul Cuffe, provides fascinating insights into the Cuff Slocum story and to the interconnections among families descended from Cuff Slocum – the Cuffes and the Wainers – and also among the families that freed him and interacted with him on his way to success as a free man – the Slocums and the Hulls.

Ruth Cuffe’s testimonial was written in 1851 about a story that she was told 53 years before in 1798 when she was only 7 years old. And the story describes events that probably occurred 53 years before that in 1745. Given such long periods between the actual events in 1745 and the transcription of the story in 1851, it is not unreasonable to expect some factual errors, but the basic story does appear to hold together if some of the key actors are reidentified.

We start off with a transcription of the full document as written by Ruth Cuffe and follow that with comments on the persons identified in it and some hypotheses as to possible corrections in the participants.[1]

As nigh as I can remember it was fifty 3 years ago that I was to work at my brother-in-law Gardner Wainer’s in Westport on the eastern side of the River and my sister wanted me to go to the store at Russeles mill in Dartmouth and buy her some things out of the store. She told me to go to Captain Hull’s store and do my trading for she had all their trading done at his store and I went for her, and when I got their, their was several men in the store and Mr. Hull told me to take a seat and sit down and wait a little while till he had waited upon them men and then he would waite upon me and as soon as they was gone out of the store he asked me what my name was. I told him that my name was Ruth Cuffe. He asked me what my father’s name was. I told him that my father’s name was David Cuffe.

Then Mr. Hull told me that my grandfather Cuffe was a slave man to his father. He told me that his father bought my grandfather Cuffe so that he should have his freedom, and his father wrote down the month and day that he purchased him and how many dollars he gave for him, and when grandfather Cuffe had worked long enough to pay for himself then his master freed him. His master paid him good wages and when he had worked long enough to pay for himself, his master gave him his freedom. The day before, he went to a Squire’s house and had a paper rote to give Cuffe his freedom and the next morning the Squire brought the paper to his house and carried the paper with him and he got there just as they were sitting down to breakfast and they all sat down and Cuffe with them and after they had some breakfast the Squire told Cuffe to take his seat as he wanted to talk with him. The Squire then asked him did he want to be a free man and be his own man. He said that he wanted to be free but he had no money to buy himself and he wanted his master not to sell him to no one and when he made his will to give his children his property to fix it so that his children never should sell him for he was afraid that he would be sold away to the west and put on the plantation. His master told him that never should be. The squire told Cuffe that he would be a free man in a few minutes. He then took the paper out of his pocket and showed it to Cuffe. The squire told Mr. Hull to write his name on the paper and he did. And then he told Hull’s wife to write her name on the same paper and she did. Then the squire gave the paper over again to Cuffe and told him he then was a free man – his own man and he must go from there that same day. Then Cuffe cried and covered himself with tears. He said that he did not know what to do and where to go he knew not. He had no home and no money for food that they had ought to let him know of it 2 or 3 weeks ago. Then it would not be so hard to him for then it was a rainy day and where to go he knew not. The squire told him that he must certainly go from there that day for that would show that he was his own free man and gone from there. The squire told him he would hire him and give him good wages. He hired him right away, and his master Hull though would hire him next month and give him good wages. The squire then gave Cuffe his paper that he wrote and told him to put into his chest in his protection carrying it with him at his house and keep it safe. Then his master that had been, gave Cuffe good advice while the squire was there. He told him to live a steady life and to take good care of his money that he was going to work for and save it so as to get him a home sometime or other. So Cuffe took 2 suits of his everyday clothes and went away from there that same day.

This Captain Hull told me at the time I was in his store and he said about the time my grandfather Cuffe had his freedom, Ruth Moses came up from Harawig, and after a while my grandfather married her. She came into Dartmouth and worked their till she married and Captain Hull told me that the Slocomes would not have my grandfather Cuffe’s children to go by the name of Slocumbes so they called them by their father’s name Cuffe. I was about seven years old when we had to go by the name of Cuffe. I remember it well.”

Family relations of persons mentioned in the story: Cuffes and Wainers

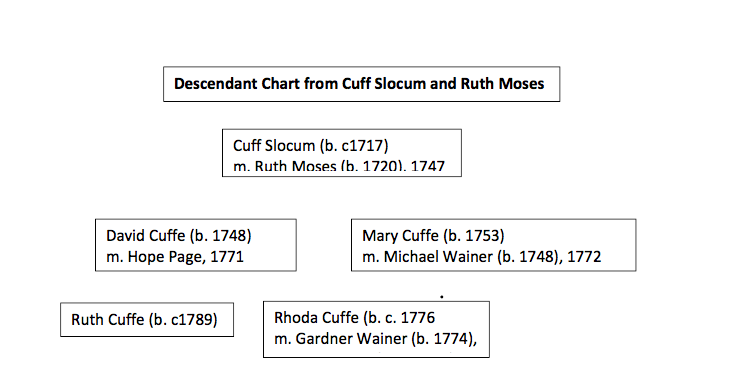

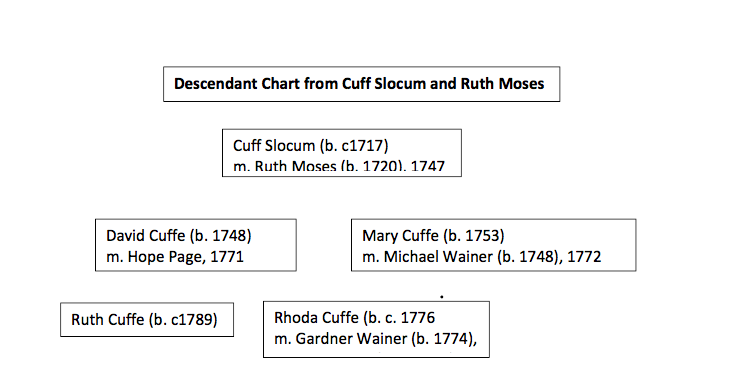

Ruth Cuffe states that she was the daughter of David Cuffe. David was the first son of Cuff and Ruth (Moses) Slocum born in Dartmouth in 1748. David married Hope Page of Freetown in 1771. His younger sister, Mary (b. 1753), married Michael Wainer (b. 1748) in 1772. David and Hope (Page) Cuffe had six children, the third being Rhoda and the fifth being Ruth. Rhoda married Gardner Wainer, the second son on Michael and Mary (Cuffe) Wainer and therefore Mary’s first cousin. Ruth Cuffe never married but lived in Indian Town in the north Westport and Troy (Fall River) border area and was reportedly a “Doctress” in later life.

[1]The copy of the statement prepared by Ruth Cuffe is from items number 668-671 in the digital version of the Cuffe Collection: Manuscript and printed material relating to Paul Cuffe, his relatives and friends from the New Bedford Free Public Library. Accessible on the <Westport.ma.com> website under the subhead Historical Documents.

Family Relationships: Hulls and Slocums

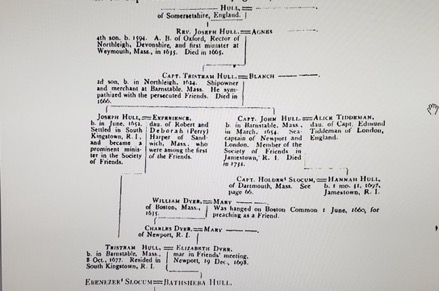

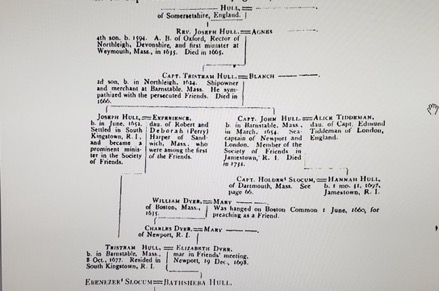

Ebenezer Slocum (b. 1705) was born in Dartmouth, MA and was the first owner of Cuff Slocum, having purchased him in Newport around 1729. He married Bathsheba Hull of Newport, RI, in Newport in 1728. Bathsheba Hull was the daughter of Tristram Hull and Elizabeth Dyer. The genealogy chart above shows the ancestors of Rebecca and Bathsheba Hull and linkages between the Hull and Slocum families in the 18thcentury

Bathsheba was the great granddaughter of Tristram Hull (b. 1624), an early settler in Barnstable, MA. Her line ran from Tristram through Joseph (b. 1651) to Tristram (b. 1677). Bathsheba was also the granddaughter of Mary Dyer who was hanged on Boston Common in 1660 for preaching Quaker heresy.

Another descendant of Tristram Hull was Hannah Hull (b. 1697) whose lineage ran from Tristram through John Hull (b. 1654). She married Holder Slocum (1697) of Dartmouth at in 1721. Holder Slocum was a cousin of Ebenezer Slocum and played an important roll in the lives of Cuff and Ruth Slocum.

Who actually told the story about Cuff Slocum?

Ebenezer Slocum sold Cuff Slocum to his nephew John Slocum (b.1717) son of Eliezer (b. 1694) who was a brother of Ebenezer Slocum. This transaction is recorded in a deed of sale dated 16 February, 1742 that also describes Cuff Slocum as a negro man of about 25 years or age. The price paid for Cuff Slocum was 150 pounds.

The freeing of Cuff Slocum from slavery and making hm a free man, as described in Ruth Cuffe’s testimonial, took place probably about three years after John Slocum purchased him in 1742. According to Ruth’s story, the owner of the store in which she was told the story was a Captain Hull, and he said that it was his father who freed Cuff Slocum many years before.

While there definitely was a store in Russells Mills at that time, around 1800, that was owned by a Captain Hull, there is clear evidence that it was not his father who freed Cuff Slocum. The deed of sale clearly establishes that it was John Slocum who purchased Cuff in 1742, and the first sentence of Cuff Slocum’s will from 1772 states that “I Cuf Slocum formerly a cervant of John Slocum and thence by him sett free and now a free man,”.

Thus, the question is who might have been the person telling the story to Ruth Slocum about the freeing of her grandfather who could rightly claim that his father had been the one to set Cuff Slocum free? Or possibly did Ruth misunderstand when Captain Hull said it was his father rather than someone else’s father.

There are two persons who were, according to the story, involved in the process – the owner and the squire. The owner was definitely John Slocum, but who was the squire? It is our belief that the squire was Holder Slocum, a prominent resident of Dartmouth and a first cousin once removed of John Slocum. Also, Holder Slocum was the person who subsequently employed Cuff Slocum to look after the livestock that were brought to the three western islands of the Elizabeth Island chain that he owned for summer grazing. He may well have hired Cuff Slocum immediately after he gained his freedom as Ruth Cuffe’s story indicates was the stated intention of the squire.

Given that John Slocum and probably Holder Slocum were the two persons who were involved in this action, it seems likely that the storyteller in Captain Hull’s store was either a son of John Slocum or a son of Holder Slocum. The fact that Holder Slocum Jr. was an executor of Captain Hulls estate along with his widow, Abigail, after his death in 1807, would seem to tip the choice toward Holder Slocum Jr. Or, Captain Hull may have been repeating a story told to him by Holder Slocum Jr.

Lineages of Holder and John Slocum

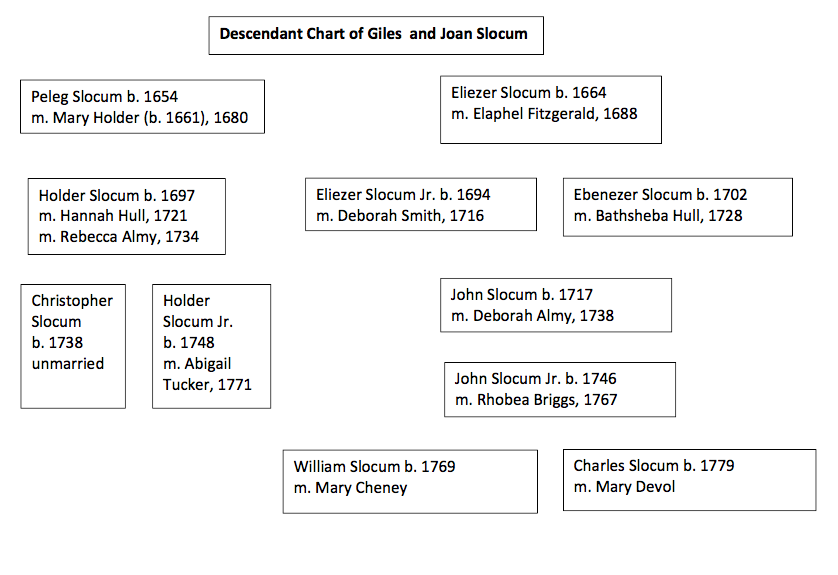

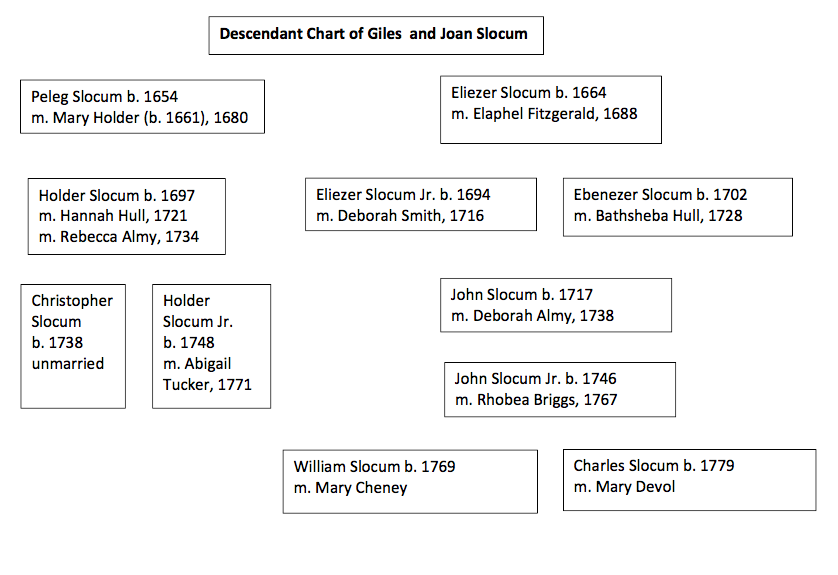

Holder Slocum (b. 1697) and Ebenezer Slocum (b. 1705) were first cousins both descendants of a common grandfather, Giles Slocum (b. c1620, d. 1682). Their fathers were Peleg (b. 1654) and Eliezer (b. 1664) respectively. John Slocum (b. 1717) was a great grandson of Giles Slocum, a grandson of Eliezer and a son of Eliezer Jr. (b. 1694).

Holder Slocum’s son, Christopher Slocum (b. 1738), inherited the three western Elizabeth Islands, Nashawena, Pasque and Cuttyhunk from his father after he died in 1758. He continued the practice of grazing sheep on those islands as indicated by his claim on his mother’s (Rebecca Almy Slocum) estate after she died in 1773 for 60 pounds for grazing her 285 sheep for three years.

John Slocum (b.1717) married Deborah Almy in Dartmouth in 1738 and they had two sons, John Jr. and William, who subsequently lived on Pasque and Nashawena.

John Slocum Jr. (b. 1746) in Dartmouth, married Rhobea Briggs on 9 October 1767 and they are reported in the Slocum genealogy to have lived on Pasque Island for several years and then moved to Nashawena where he died in in 1818. It is not clear whether they moved to Pasque immediately after their marriage, but it is worth noting that their marriage occurred in the same year that Cuff Slocum moved his family from Cuttyhunk to their new farm in Dartmouth. It is conceivable that John Slocum Jr. took over responsibility for overseeing sheep grazing activities on his uncle Holder Slocum Jr.’s three western islands.

William Slocum (b. 1769) married Mary Cheney in 1792. He was a master-mariner for many years and later in life a farmer with residence on Nashawena Island.

We have not been able to establish the relationship between the Captain Hull who owned the store in Russells Mills in 1800 and the previous Hulls, Rebecca and Bathsheba, who were descended from Tristram Hull (1624) and married to Holder and Ebenezer Slocum respectively. But we will keep searching.

Some interesting stories about activities of various Slocums on the Elizabeth Islands

There are several interesting stories in the Slocum genealogy and in the book about the Elizabeth Islands by Alice Forbes Howland that are worth retelling because they are from sources that are not easily available. The first is from the sketch of Holder Slocum Sr. in the Slocum genealogy (pp. 67-8).

Holder Slocum Sr. providing a shallop for Quaker minister to sail to Nantucket.

“Thomas Chalkley, a distinguished minister in the Society of Friends, wrote that Holder Slocum was prominent among Friends as early as the time of his marriage with Captain Hull’s daughter. Thomas Chalkley visited Dartmouth, Mass., in the year 1737, and was entertained at the house of Captain Slocum. HisJournal,on that occasion, contains the following entry:

‘Holder Slocum lent us his shallop to go over to Nantucket; but the wind not favoring, we had a satisfactory meeting at a large farm of his on an island bearing his own name, and after the meeting set sail for Nantucket; had several large meetings there, and I rejoiced to see the growth and increase of Friends on the island, where God hath greatly multiplied his people and made them honorable.’

Slocum’s Island, referred to above, was probably one of the Elizabeth group in Buzzard’s Bay. Holder’s wife Hannah died at her father’s house in Jamestown, Rhode Island, the 28thof eighth month, 1725 and was buried there in Friends’ ground. He was published, for second marriage, to Rebecca Almy of Tiverton, R. I., the 4thof the First month, 1733 or ’34.”

This sketch attests to several interesting facts.

- Shallops were both a common term and a popular small sailing and rowing craft used along the New England Coast for traveling along the coast and to the nearby islands.

- Holder Slocum had a “large farm” on one of the Elizabeth Islands, probably either Nashawena or Pasque, in 1737. It is not clear what kind of farm it was, e.g. a sheep station for warm weather grazing, or something else. Also, it is not clear how many people were living on the island, whether they lived there year-round or whether there were substantial dwellings, but it does suggest that there were some people residing there for at least part of the year at that time.

More insights on the activities of the Slocums on the Elizabeth Islands

The insights from the Slocum genealogy are further reinforced by excerpts from the book by Alice Forbes Howland: Three Islands: Pasque, Nashawena and Penikese(pp 57-60).

“Although Peleg Slocum seems to have owned Nashawena from 1693 until it was acquired by his son Holder in 1742, it would not appear that he ever lived on the island and it is pretty clear that he lived on his big farm at Barney’s Joy across the Bay. He evidently owned at least one boat which he sailed himself, occasionally to Nantucket to hold or attend Quaker meetings.

Nashawena and Cuttyhunk afforded good summer grazing in those days, and cattle were taken over from the mainland in boats each spring and brought back in the autumn. The old stone pound where the cattle were rounded up for these trips is still standing (1964) near the mouth of Slocum’s River, and it may be supposed that Peleg sent his own cattle over to the island, and perhaps those of some of his neighbors as well, for which grazing privileges they would have paid him a fee.

Peleg died in 1733 at the age of 79. In 1743 Peleg’s son Holder, then 46 years old, came into possession of part of the east end of Nashawena from ‘fellmonger’ (a dealer in sheepskins or other hides) Thomas Bailey and others. Eight years later in 1751, Holder acquired all of the land on Nashawena, Cuttyhunk and Penikese that Peleg had owned…. We know little of Holder’s activities or if he ever lived on the island, but inasmuch as his son, Holder Jr. is listed as ‘of Dartmouth’ in a Court Record in 1794 against John Slocum of Chilmark (remember that Nashawena belonged to Chilmark in those days), it would seem that Holder Jr. owned the island but lived on the mainland while John lived either on Nashawena or Pasque.

Now comes a gap in our story as there appears to be nothing to tell us what happened on Nashawena or who was living there from 1745 to the time of the Revolution. As early as 1775 the British Sloop of War Faulkland made a surprise visit to the Elizabeth Islands and seized livestock from Naushon and Pasque, and it is more than likely that they took cattle, sheep and hogs from Nashawena as well; so those years when British warships were continually in the waters of the Bay and Sound must have been a time of fear and deprivation for the people living on the islands.”

In an earlier part of her story, Howland reports that life on Pasque and Nashawena was not always so dismal or uninteresting. In her chapters on Pasque, she tells the following story (pp. 6-7):

“Pasque was the scene of a small but relatively important intrigue in 1779 when a group of British officers from a fleet lying in Tarpaulin Cove ‘spent the evening of April 2ndin a frolic at the house of John Slocum on Pesque (sic) Island” Now, Slocum was a Quaker and well-known for his Tory sympathies, but after hearing his ‘guests’ discussing plans to attack and burn Falmoth the following day, loyalty to his neighbors overcame his Tory leanings, and he sent a messenger secretly down the island and across to the mainland the warn the people there of their danger. The British met a well-organized force of militia, which had been hastily summoned from Barnstable and Sandwich, and were successfully repulsed; and they must have wondered how their plans – laid so carefully two islands and ten miles away – could have been anticipated.”

Before she died in 1773, Rebecca Slocum was billed by her son, Christopher Slocum, for 60 pounds for grazing her 285 sheep on Cuttyhunk for three years. This obligation was listed in her inventory after her death. Christopher, the oldest son of Holder and Rebecca Slocum, had inherited Cuttyhunk from his father and later passed it and other properties in the Elizabeth Islands along to his two brothers, Peleg and Holder Slocum Jr.. This bill indicates that the annual charge for grazing this number of sheep was 20 pounds. Unfortunately, we have no way of estimating how many sheep might have been grazing on the western Elizabeth Islands that Christopher Slocum and his brothers owned at that time.

Also included in the inventory of Rebecca Slocum’s estate was a “ferryboat lying at Christopher Slocum’s wharf together with her anchor, rigging, sails and appurtenances” valued at 43 pounds, 6 shillings and 8 pence. This would be a reasonable description of a shallop.

What can we learn from these stories?

- Peleg Slocum owned at least Nashawena from 1693 until his death in 1743 when it passed to his oldest son, Holder Slocum. But Holder appears, according to Rev. Chalkley’s story, to have been in charge of activities there in 1733 which included some kind of a farm.

- Holder Slocum inherited at least parts of Nashawena from his father and by 1751 owned all of the three islands – Nashawena, Cuttyhunk and Penekise. Alice Howland says that there is no record of what happened on these islands between 1751 and 1775 when the British Navy raided them and took away livestock.

- From our previous research we can fill this gap that links into Ruth Cuffe’s testimonial. Cuff Slocum and Ruth Moses were married in Dartmouth in 1747 and had their first two children, David and Jonathan in Dartmouth in 1748 and 1749. Their third child, Sarah was born in 1752 on Cuttyhunk. Cuff and Ruth Slocum had their next seven children on Cuttyhunk from 1753 to 1766. We have concluded that Cuff was working for Holder Slocum looking after the livestock, mainly sheep, that were brought to at least Cuttyhunk and Nashawena during those years. The family moved to Dartmouth in the spring of 1767 to a 116-acre farm they had purchased from David Brownell for 650 Spanish milled silver dollars, equal to about 200 British pounds. We also know from the Slocum genealogical story that John Slocum (b. 1746) married Rhobea Briggs in 1667 and that they moved to Pasque sometime thereafter. Whether they took over management of the livestock grazing activities on the western Elizabeth Islands from Cuff Slocum we don’t know, but we do have the evidence, from Christopher Slocum’s claim on his mother’s estate in 1773 for three years of grazing 285 of her sheep on Cuttyhunk, that such livestock (probably mainly sheep) grazing continued up until that time. And then the British raid on several Elizabeth Islands in 1775 to take livestock confirms the continuing practice.

- John and Rhobea Slocum were still living on Pasque in 1779 when they entertained the British naval officers in their home and then alerted the people of Falmouth to the impending attack the next day.

- There is no record of when John Slocum and his family moved to Nashawena. It may have been sometime during the Revolutionary War. But it is clear that this Slocum family, and possibly others were living on the western Elizabeth Islands during the war and John is said to have been a loyalist.

- It is worth noting that during these war years, Paul Cuffe, the son of Cuff Slocum whom John Slocum Jr.’s father, John Slocum Sr. had granted his freedom, was sailing through these western Elizabeth Islands, probably in a shallop borrowed from one of the Dartmouth-based Slocums, to deliver supplies to the Quaker and partly loyalist inhabitants of Nantucket. It would be surprising if Paul Cuffe did not have some interactions with the John Slocum family on those islands during his travels back and forth.

- The court record from 1794 of Holder Slocum Jr. (b. 1748) of Dartmouth suing his cousin John Slocum, probably John Slocum Jr. (b. 1746) of Chilmark, suggests that these cousins were not always able to settle their affairs amicably and also that John Slocum was still engaged in activities on probably Nashawena that was then owned by his cousin, Holder Jr..

References:

Bosworth, Janet. Cuttyhunk and the Elizabeth Islands from 1602.Cuttyhunk Historical Society, Cuttyhunk, Massachusetts. 1993.

Cuffe, Paul. Paul Cuffe Manuscript Collection at the New Bedford Free Public Library. New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Howland, Alice Forbes. Three Islands: Pasque, Nashawena and Penikese. Boston, Pinkham Press, 1964.

Pierce, Andrew & Jerome D. Segel. Wampanoag Families of Martha’s Vineyard.Heritage Books, 2016.

Slocum, Charles Elihu. A Short History of the Slocums, Slocumbs and Slocombs of America, Genealogical and Biographical, from 1637 to 1881.Syracuse, N.Y. published by the author, 1882.